Set-Operations with Overlay¶

When working with multiple spatial datasets – especially multiple polygon or

line datasets – users often wish to create new shapes based on places where

those datasets overlap (or don’t overlap). These manipulations are often

referred using the language of sets – intersections, unions, and differences.

These types of operations are made available in the geopandas library through

the overlay function.

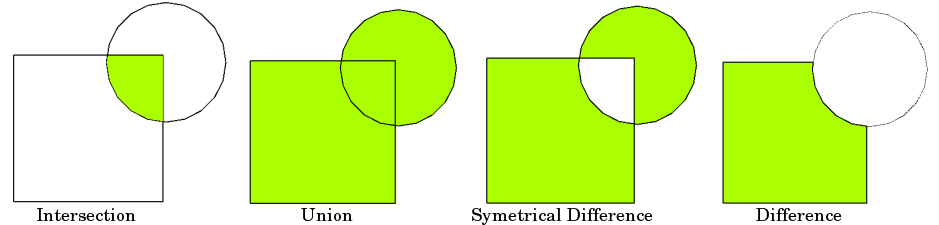

The basic idea is demonstrated by the graphic below but keep in mind that overlays operate at the DataFrame level, not on individual geometries, and the properties from both are retained. In effect, for every shape in the first GeoDataFrame, this operation is executed against every other shape in the other GeoDataFrame:

Source: QGIS Documentation

(Note to users familiar with the shapely library: overlay can be thought

of as offering versions of the standard shapely set-operations that deal with

the complexities of applying set operations to two GeoSeries. The standard

shapely set-operations are also available as GeoSeries methods.)

The different Overlay operations¶

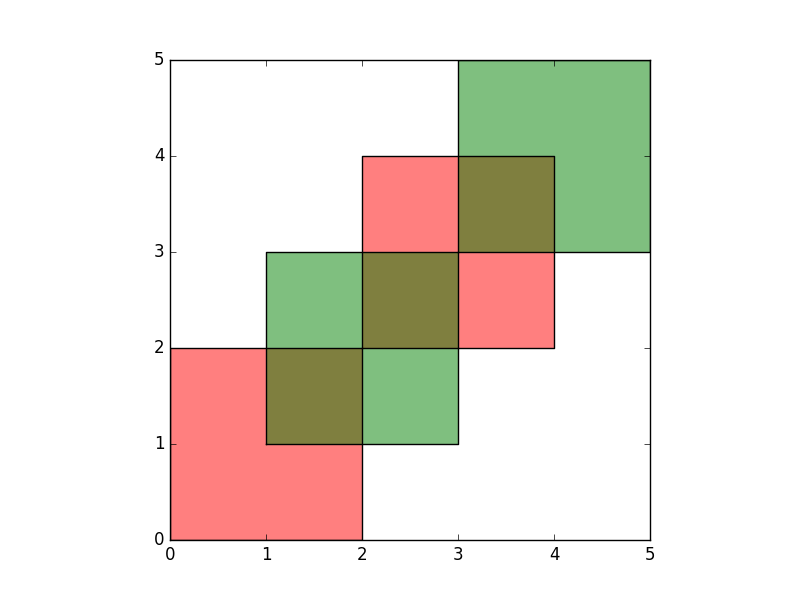

First, we create some example data:

In [1]: from shapely.geometry import Polygon

In [2]: polys1 = gpd.GeoSeries([Polygon([(0,0), (2,0), (2,2), (0,2)]),

...: Polygon([(2,2), (4,2), (4,4), (2,4)])])

...:

In [3]: polys2 = gpd.GeoSeries([Polygon([(1,1), (3,1), (3,3), (1,3)]),

...: Polygon([(3,3), (5,3), (5,5), (3,5)])])

...:

In [4]: df1 = gpd.GeoDataFrame({'geometry': polys1, 'df1':[1,2]})

In [5]: df2 = gpd.GeoDataFrame({'geometry': polys2, 'df2':[1,2]})

These two GeoDataFrames have some overlapping areas:

In [6]: ax = df1.plot(color='red');

In [7]: df2.plot(ax=ax, color='green');

We illustrate the different overlay modes with the above example.

The overlay function will determine the set of all individual geometries

from overlaying the two input GeoDataFrames. This result covers the area covered

by the two input GeoDataFrames, and also preserves all unique regions defined by

the combined boundaries of the two GeoDataFrames.

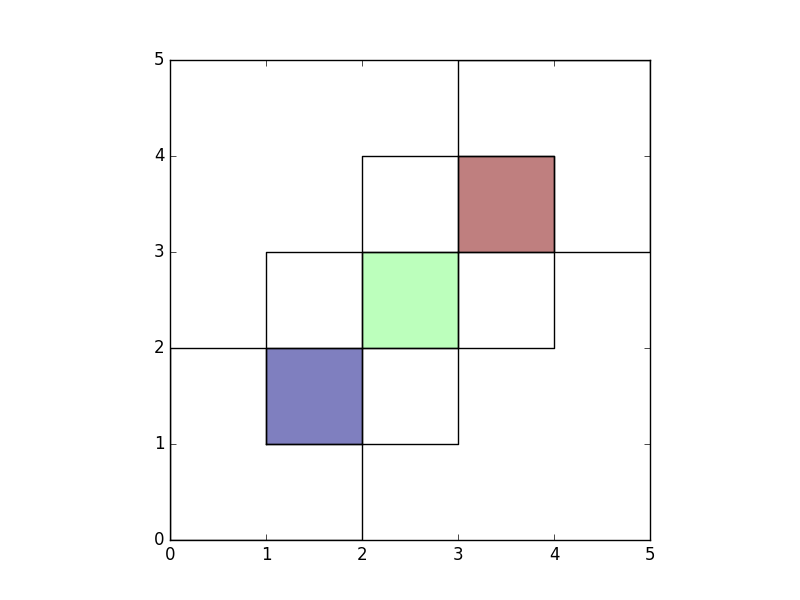

When using how='union', all those possible geometries are returned:

In [8]: res_union = gpd.overlay(df1, df2, how='union')

In [9]: res_union

Out[9]:

df1 df2 geometry

0 1.0 NaN POLYGON ((2 1, 2 0, 0 0, 0 2, 1 2, 1 1, 2 1))

1 1.0 1.0 POLYGON ((2 1, 1 1, 1 2, 2 2, 2 1))

2 NaN 1.0 POLYGON ((2 1, 2 2, 3 2, 3 1, 2 1))

3 NaN 1.0 POLYGON ((2 2, 1 2, 1 3, 2 3, 2 2))

4 2.0 NaN POLYGON ((3 2, 3 3, 4 3, 4 2, 3 2))

5 2.0 1.0 POLYGON ((3 3, 3 2, 2 2, 2 3, 3 3))

6 2.0 NaN POLYGON ((3 3, 2 3, 2 4, 3 4, 3 3))

7 NaN 2.0 POLYGON ((4 3, 4 4, 3 4, 3 5, 5 5, 5 3, 4 3))

8 2.0 2.0 POLYGON ((3 4, 4 4, 4 3, 3 3, 3 4))

In [10]: ax = res_union.plot()

In [11]: df1.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='none');

In [12]: df2.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='none');

The other how operations will return different subsets of those geometries.

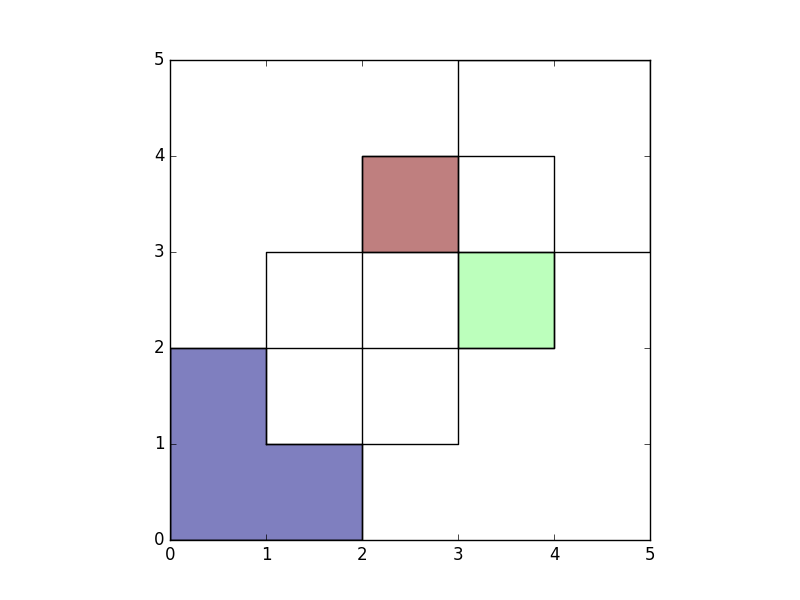

With how='intersection', it returns only those geometries that are contained

by both GeoDataFrames:

In [13]: res_intersection = gpd.overlay(df1, df2, how='intersection')

In [14]: res_intersection

Out[14]:

df1 df2 geometry

0 1 1 POLYGON ((2 1, 1 1, 1 2, 2 2, 2 1))

1 2 1 POLYGON ((3 3, 3 2, 2 2, 2 3, 3 3))

2 2 2 POLYGON ((3 4, 4 4, 4 3, 3 3, 3 4))

In [15]: ax = res_intersection.plot()

In [16]: df1.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='none');

In [17]: df2.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='none');

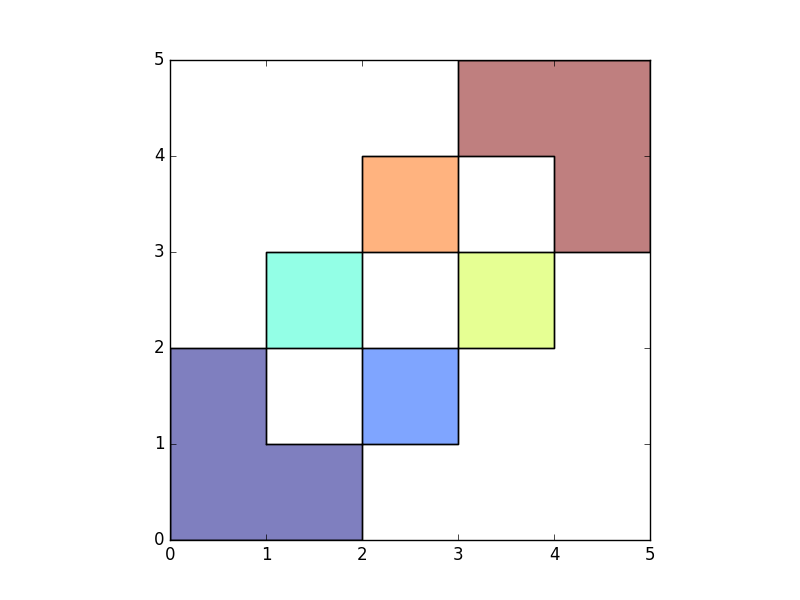

how='symmetric_difference' is the opposite of 'intersection' and returns

the geometries that are only part of one of the GeoDataFrames but not of both:

In [18]: res_symdiff = gpd.overlay(df1, df2, how='symmetric_difference')

In [19]: res_symdiff

Out[19]:

df1 df2 geometry

0 1.0 NaN POLYGON ((2 1, 2 0, 0 0, 0 2, 1 2, 1 1, 2 1))

1 NaN 1.0 POLYGON ((2 1, 2 2, 3 2, 3 1, 2 1))

2 NaN 1.0 POLYGON ((2 2, 1 2, 1 3, 2 3, 2 2))

3 2.0 NaN POLYGON ((3 2, 3 3, 4 3, 4 2, 3 2))

4 2.0 NaN POLYGON ((3 3, 2 3, 2 4, 3 4, 3 3))

5 NaN 2.0 POLYGON ((4 3, 4 4, 3 4, 3 5, 5 5, 5 3, 4 3))

In [20]: ax = res_symdiff.plot()

In [21]: df1.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='none');

In [22]: df2.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='none');

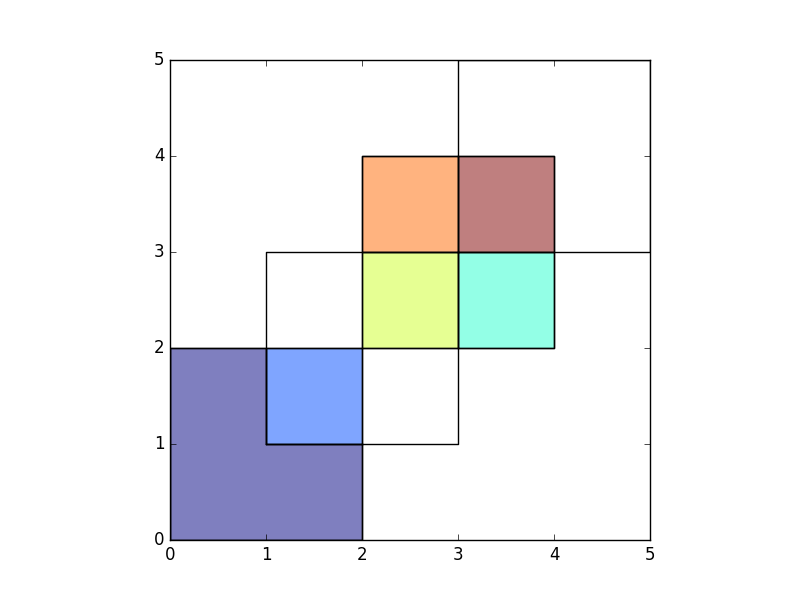

To obtain the geometries that are part of df1 but are not contained in

df2, you can use how='difference':

In [23]: res_difference = gpd.overlay(df1, df2, how='difference')

In [24]: res_difference

Out[24]:

df1 df2 geometry

0 1 None POLYGON ((2 1, 2 0, 0 0, 0 2, 1 2, 1 1, 2 1))

1 2 None POLYGON ((3 2, 3 3, 4 3, 4 2, 3 2))

2 2 None POLYGON ((3 3, 2 3, 2 4, 3 4, 3 3))

In [25]: ax = res_difference.plot()

In [26]: df1.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='none');

In [27]: df2.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='none');

Finally, with how='identity', the result consists of the surface of df1,

but with the geometries obtained from overlaying df1 with df2:

In [28]: res_identity = gpd.overlay(df1, df2, how='identity')

In [29]: res_identity

Out[29]:

df1 df2 geometry

0 1 NaN POLYGON ((2 1, 2 0, 0 0, 0 2, 1 2, 1 1, 2 1))

1 1 1.0 POLYGON ((2 1, 1 1, 1 2, 2 2, 2 1))

2 2 NaN POLYGON ((3 2, 3 3, 4 3, 4 2, 3 2))

3 2 1.0 POLYGON ((3 3, 3 2, 2 2, 2 3, 3 3))

4 2 NaN POLYGON ((3 3, 2 3, 2 4, 3 4, 3 3))

5 2 2.0 POLYGON ((3 4, 4 4, 4 3, 3 3, 3 4))

In [30]: ax = res_identity.plot()

In [31]: df1.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='none');

In [32]: df2.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='none');

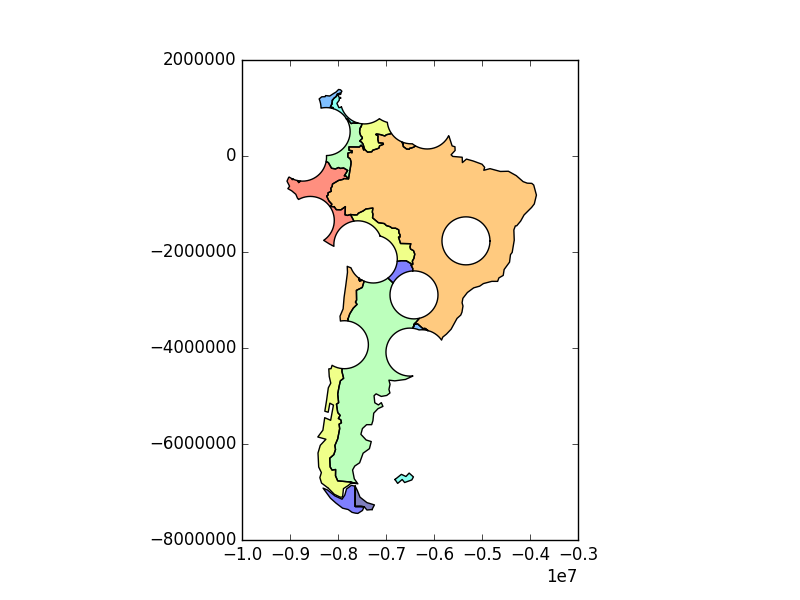

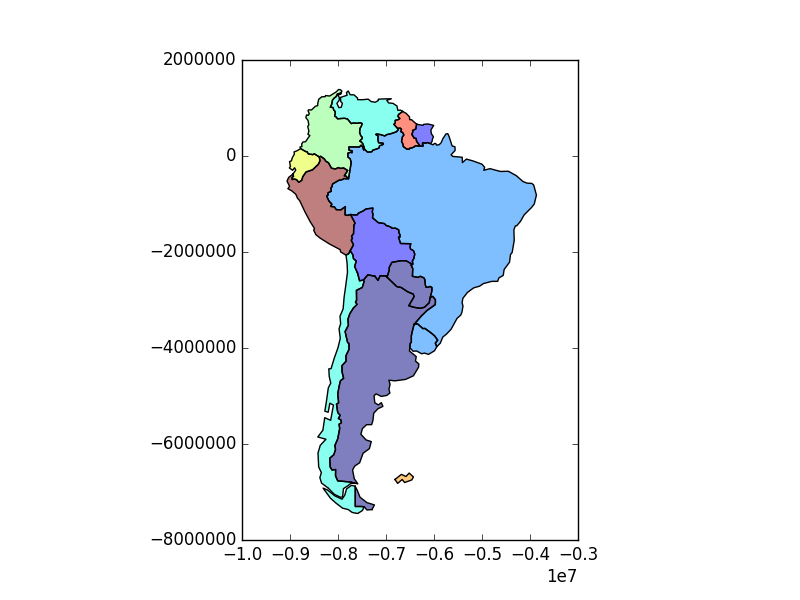

Overlay Countries Example¶

First, we load the countries and cities example datasets and select :

In [33]: world = gpd.read_file(gpd.datasets.get_path('naturalearth_lowres'))

In [34]: capitals = gpd.read_file(gpd.datasets.get_path('naturalearth_cities'))

# Select South Amarica and some columns

In [35]: countries = world[world['continent'] == "South America"]

In [36]: countries = countries[['geometry', 'name']]

# Project to crs that uses meters as distance measure

In [37]: countries = countries.to_crs('+init=epsg:3395')

In [38]: capitals = capitals.to_crs('+init=epsg:3395')

To illustrate the overlay function, consider the following case in which one

wishes to identify the “core” portion of each country – defined as areas within

500km of a capital – using a GeoDataFrame of countries and a

GeoDataFrame of capitals.

# Look at countries:

In [39]: countries.plot();

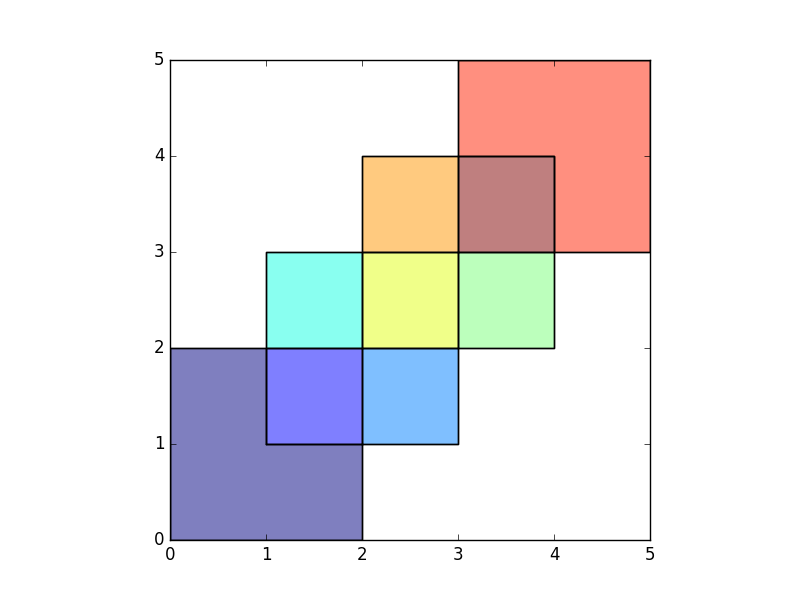

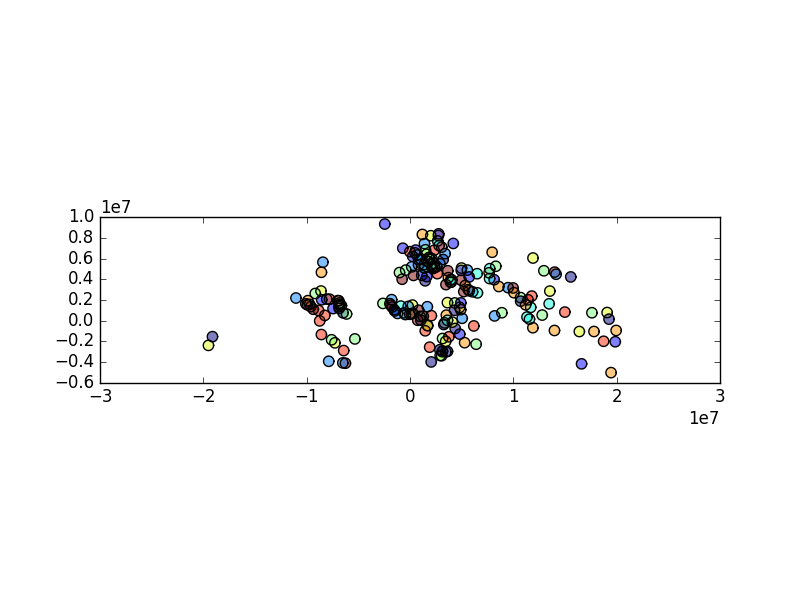

# Now buffer cities to find area within 500km.

# Check CRS -- World Mercator, units of meters.

In [40]: capitals.crs

Out[40]: '+init=epsg:3395'

# make 500km buffer

In [41]: capitals['geometry']= capitals.buffer(500000)

In [42]: capitals.plot();

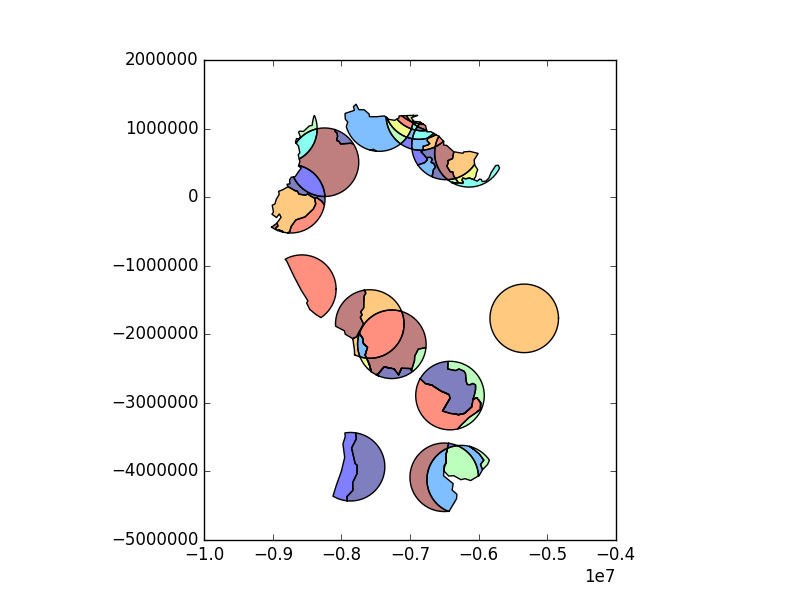

To select only the portion of countries within 500km of a capital, we specify the how option to be “intersect”, which creates a new set of polygons where these two layers overlap:

In [43]: country_cores = gpd.overlay(countries, capitals, how='intersection')

In [44]: country_cores.plot();

Changing the “how” option allows for different types of overlay operations. For example, if we were interested in the portions of countries far from capitals (the peripheries), we would compute the difference of the two.

In [45]: country_peripheries = gpd.overlay(countries, capitals, how='difference')

In [46]: country_peripheries.plot();